3 Primary Themes in Early Concept Testing

Using the CUB framework to focus research attention for early product concepts

As tech companies develop new products and features, they’ll typically want user feedback to revise and validate concepts. Testing product concepts early and often helps to pivot ideas without wasting too many resources. But where should a researcher focus their questioning when there’s not yet an interactive prototype to run a full usability test with?

Some of the most crucial feedback—especially when it comes to testing early concepts—centers around value and basic functionality. Do prospective users agree that a team’s new idea will help to improve their experience?

One of the most widely used research methods for collecting this feedback is a qualitative user interview, but it’s not always easy to keep an interviewee’s attention focused on value. Generic questions such as “what do you most like/dislike about this concept?” will often be met with comments about visual design such as preferred colors or text layout.

Feedback about visual design is of course valuable but it’s usually not the main priority in early testing, especially since designs are intended to be rough and immature. Value and basic functionality are the hardest-hitting questions when seeking early signs of product-market fit.

Based on studying how researchers around the industry prioritize questions in concept testing and how much value my own product teams have derived from research insights in the past, I think there’s a small set of broadly-applicable and high-impact themes to rely on. Although there are hundreds of individual questions you could ask about value and functionality, the most common and actionable ones tend to cluster into three primary domains, which I will outline here.

The CUB themes

In the visual below, you’ll see three simple themes that are relevant from the earliest stages of concept testing: comprehension, utility, and barriers (let’s call this the CUB framework after my favorite baseball team). This generally excludes deeper questions about technical usability or visual design, which might be more relevant for an advanced and interactive prototype. Instead, the researcher might have a few mock screens to demonstrate the functionality of a new idea or even just a pen-and-paper sketch. In any case, the purpose is to get early signal on whether a high-level product idea is worth investing more time in.

Since every researcher and/or product team will have their own specific needs and nuances to incorporate into testing, this framework isn’t a research plan or blueprint. Think of it more as a sensible starting point for deciding where to focus research time and how to build out more specific questions or areas to cover (the example questions in each section are merely concise illustrations of what each theme refers to, not interview questions).

Comprehension

The first theme above targets what people understand from the idea you’re showing or discussing. You generally want to avoid saying too much about the product idea before this stage, since the purpose is to get people’s spontaneous reactions and perceptions of the concept. Does the idea confuse them? Do they immediately latch on to a particular element of it as clear or exciting? Are they generally describing it in a way that matches the product team’s plans and expectations?

Comprehension is important as a first step because without it, there’s a risk that people end up describing their reactions and expectations to something entirely different to what the product team has in mind. I know from bitter personal experience that unaddressed confusion at the start of an interview can lead to a full 30 mins of misaligned conversation that produces nothing actionable.

So start by asking people to tell you what they’re seeing, thinking, and understanding about the idea in front of them without probing too much. At the end of the section, you can then clarify confusions and maximize alignment for the next steps of the research interview, while taking the user’s first impressions back to the team to incorporate into design revisions.

Utility

After interviewer and interviewee are on the same page about what the idea is and what it’s supposed to do, you can talk about user needs and motivations. I’d consider this the highest priority and usually the most time-consuming segment of the wheel above. If users understand the idea but can’t link it with a clear need in their life, the idea is probably dead in the water.

Utility drives usage since products are generally designed to solve problems. It helps to get super specific with people about whether they have any specific motivations related to the proposed product or feature. Can they think of specific examples in the last couple of weeks where they experienced a problem or inconvenience that the product would have helped with? Do they use other products or services that already solve the need they find most relevant for the concept?

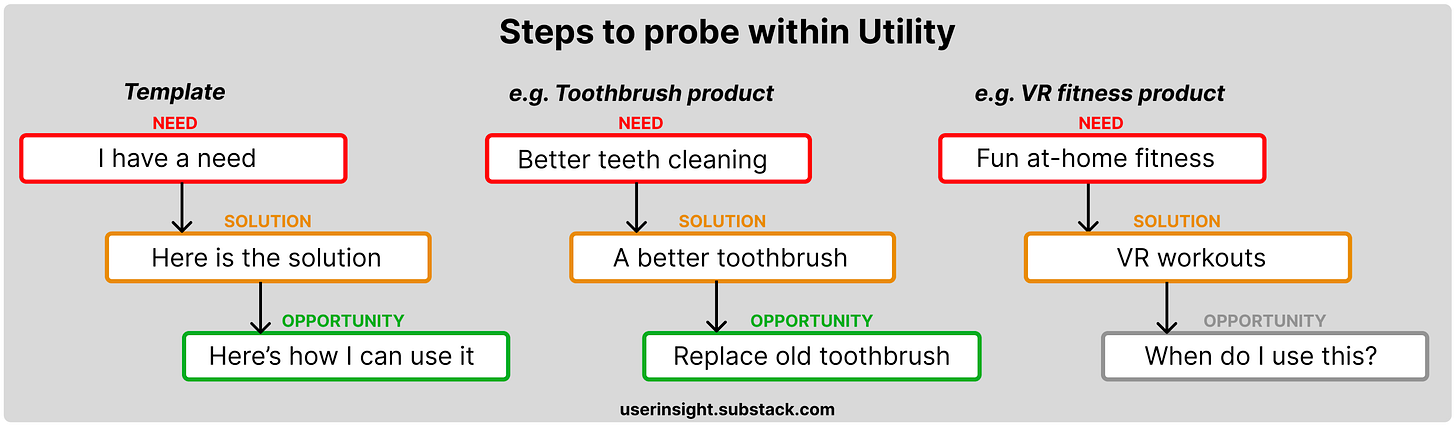

Unmet needs are particularly important to touch on here because you want to know if there’s a competing product (or even a competing feature within your own product) that consumes the demand you’re trying to address or create with the new concept. At the same time, you want to distinguish between how much people are convinced that they have a particular unmet need vs how much they believe the solution they’re currently looking at is the right one to meet it. Sometimes, research participants get so passionate about how important a problem is for them that it’s misinterpreted as passion for the proposed solution.

Getting people’s thoughts on how the product might fit into their lives is a helpful focus and can help to clarify these ambiguities. It forces people to come up with specific scenarios where they’ve experienced a problem, and then explicitly consider how the proposed solution may or may not have helped. This gives them the mental space to realize either “I would use this product whenever X happens because it’ll solve for Y” or “this is definitely an important problem in my life, but I’m not sure this solution would work for me”.

This issue has come up frequently when I’ve worked with startups. They often have cool products that are designed to solve high-priority unmet needs for users, and yet, when it comes down to actual adoption and retention after launching the product, things don’t seem to click for people in their daily usage. There has to be not only a real need to use a product, but also a compelling example of how the product solves that need given a specific opportunity.

One month ago, I ordered a new, improved electric toothbrush, and I’ve used it twice a day without fail ever since. It was easy to fit into my normal schedule by replacing my old toothbrush and gaining a small dental hygiene benefit. I had a clear need (cleaner teeth), a clear solution (efficient tool for cleaning teeth), and plenty of easy opportunity (brushing twice a day).

On the other hand, despite gaining significant value recently from VR workouts, I’ve been struggling to create a reliable habit or pattern that I can stick to each day, because it takes time to go into my workout space to set everything up, and I’m not always free at the same time (yes, I do have children). I have a clear need (keeping fit), a clear solution (fun cardio activities), but less clear opportunities (lack of easy space/time for a new habit). The VR workouts provide more value for me than an improved toothbrush, but I’ve used the latter more reliably just because it straightforwardly checks all the boxes.

People aren’t always great at anticipating their future selves and habits, but there’s nothing wrong with asking for their early thoughts. Occasionally, you’ll find a consistent theme that you didn’t know existed in relation to how people expect to use the product, and you can leverage that in how you launch or market the product going forward.

Barriers

A final theme that’s always productive to cover in early concept testing is related to barriers. These might be hesitations in adopting the product, expected frictions in using it, or other specific doubts about value. This theme gives people the opportunity to share what they believe to be downsides or obstacles to using the product and any suggestions for improving how it fits with their own needs.

This theme yields impactful insights when it successfully identifies prominent reasons for why people might avoid the product. For example, if people worry about safety with a ride-hailing app, perhaps product strategy can focus more on communicating driver verifications and offering new call-for-help features. If some people are avoiding a vaccine because they fear the pain of the procedure, perhaps informational campaigns directed at them should highlight how little the procedure hurts rather than purely the health benefits. If customers say they find online streaming more convenient than video rental, perhaps Blockbuster should acquire Netflix.

In the past, product teams I’ve worked with have killed product ideas swiftly when early concept testing raised a critical user concern that they hadn’t previously considered. In one case, a key segment of users said they wouldn’t use a specific type of privacy feature because it would negatively impact their business growth. In another, participants said they didn’t care about a prospective user metric in a fitness product because it seemed too artificial. In another, participants said they didn’t feel swayed by an informational campaign designed to change their mind because it focused on long-term benefit when they were more worried about short-term cost. In all of these cases, the emergent qualitative theme was enough to convince teams to rethink their solution.

We’d all love a superpower that allows us to forecast which products will fail and why. Asking about barriers in a research interview isn’t quite that superpower, but it’s certainly one practical signal that can support more informed decision-making.

❗️Feedback wanted❗️

I wanted to say a huge thank you to everyone who recently signed up here. I hope much of what I write will be helpful to you, but please know that I gain just as much from hearing your thoughts as you do from hearing mine. I’m just one guy in research, and I can see a whole bunch of subscribers with interesting backgrounds related to building products and/or discovering great insights. So please don’t hesitate to share your feedback and comments on this and any other post.

Have you found something I said particularly valuable in your own work? Can you share examples or stories related to something I wrote? Is there anything specific you’d add to one of my suggestions that others can benefit from? Anything you want to reinforce, criticize, or request from me?

All comments are very welcome and appreciated. When you share something that I think is important to mention more broadly, I’d love to include your comment in an upcoming User Insight post (if you want me to!).

“Nothing has such power to broaden the mind as the ability to investigate systematically and truly all that comes under thy observation in life.”

~ Marcus Aurelius

If you enjoyed this newsletter, please spread the word by sharing it with others who might find value in it. If you’re new here, you can subscribe below.

Thanks so much for sharing this! I love the framework - it's simple and helps ensure we, as researchers, are covering crucial points related to product development as early as possible in the process.

Great insights, Erman! I especially loved the discussion on utility. You really hit it on the nose that if you ask a participant if they will use a cool new product, they'll likely say yes. But what we want to understand as researchers is if the product will actually be valuable to them. Having them describe how they might use it in their day-to-day life is a great way to suss out whether a participant just thinks an idea is cool or if it would actually be a value add to them. Thanks for sharing this!